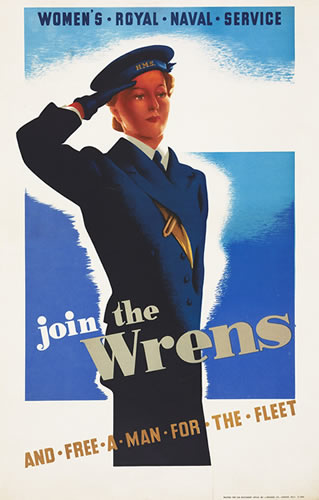

The ‘Wrens’, or members of the WRNS (Women’s Royal Naval Service) worked alongside men in the navy in both world wars. The WRNS was formed in November 1917 and its members served together with the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) and later the Women’s Royal Air Force.

The Wrens of World War 1

The Wrens initially served from 1917 to 1919 during the first world war. In a world where nothing more was expected of women than to be a wife and mother, their sudden eruption into the settled male ranks of the armed services caused a major stir. But they caused an even bigger stir by proving to be very good at the many tasks they were set, demonstrating a high degree of competence and hard work which set a marker for the future.

As ‘returning heroes’, millions of returning servicemen at the end of the Great War replaced women in industry, the armed services and other working areas, despite the competence that these women had shown during the war. The Admiralty decreed that the Wrens had to be closed and despite fierce opposition from the women themselves the WRNS ceased to be in 1919. But their success in filling the many gaps left by men going off to fight was not forgotten.

The Wrens of World War 2

in 1939 the WRNS was reconstituted with World War 2 looming. At first the fine old admirals simply asked for 1,500 part time women to fulfil domestic chores. By the war’s end there were over 54,000 Wrens serving in many countries and performing a multitude of tasks. The Royal Navy was, by some margin, the most reactionary and hidebound of the three fighting services and resistance to the Wrens never went away completely, however the majority of the navy accepted the Wrens. As in World War One, the ladies proved to be reliable, competent and hard working; it was rare for any Wren to not perform their tasks well.

What did the Wrens do?

The original expectation of 1500 domestics was rapidly overtaken by events. Throughout the Second World War the Royal Navy suffered from manpower shortages and where gaps appeared, the Wrens stepped in. At first that was an extension of traditional ‘women’s work’ such as secretarial and an all-encompassing role in domestic work. Soon, however, many more jobs were taken on, from coding and cypher work through signalling and radio telegraphy to a host of manual jobs. Ships were repaired by Wrens, torpedoes maintained and fitted in submarines, Fleet Air Arm planes were repaired, maintained and even flown in, parachutes were packed, and so many other specialisations.

And in the most coveted job of all were the 500 or so Wrens who made up crews for the Navy’s launches and small boats. These women came close to being fully fledged seamen, working well beyond harbour limits, trained to fire Lewis guns, working day and night in all weathers and often in danger. Although this contingent often lacked formal discipline, they still excelled at their jobs and were therefore well-respected.

Wren Jane Beacon book

The Wren Jane Beacon series of novels follows the career of one particularly successful but argumentative Wren from the early days of the war and shows what was expected of these girls as they went about their business. The book highlights how the seagoing Navy took them to their hearts so much that they became a fully integrated part of the Navy, not seen as any different from men working in the same roles.